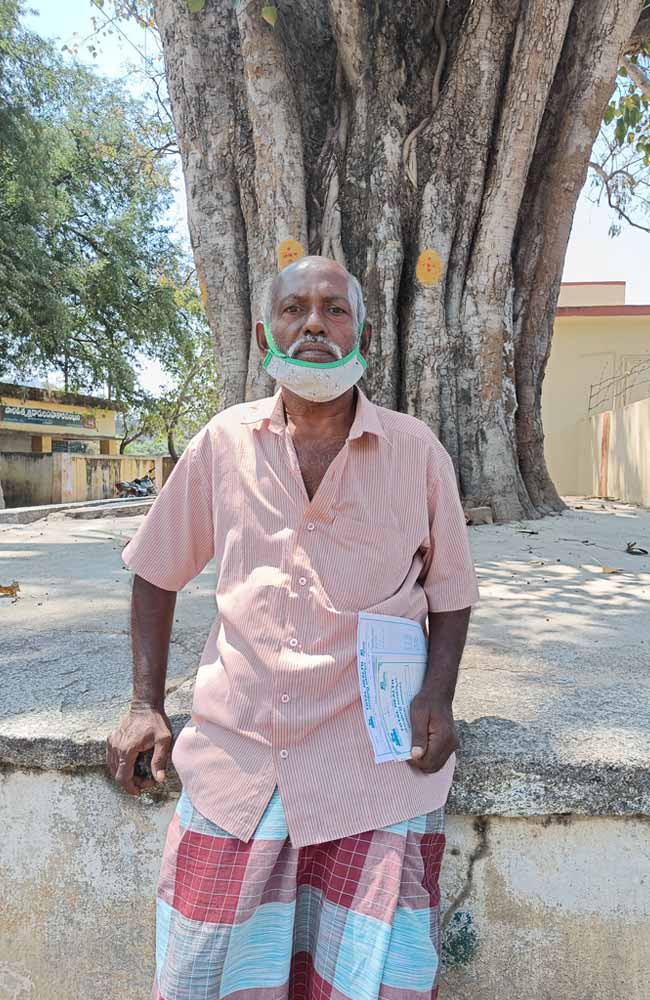

At a healthcare clinic in Thodathara, a village in the Thavanampalle mandal near Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, Dr Vijay Kumar calls in his next patient. “He is the most disciplined man I know,” Dr Kumar says with a hint of pride.

Reddyappa Reddy walks in and takes the seat opposite Dr Kumar. “Ten years ago I found out I have diabetes. I took Dr Kumar’s advice. Today, I walk up and down the lengths of a mango farm every day after dinner,” says Reddyappa, who is in his sixties. Dr Kumar adds that Reddy is an inspiration to the other patients at the clinic.

The numbers game

IIn 2013, Apollo Foundation’s Total Health initiative conducted a household survey of 195 villages and 32 gram panchayats in the Thavanampalle mandal. We screened 31,453 people for health data and found that 6.2 percent had diabetes. In addition, 16.7 percent of men and 12.2 percent of women were obese, a risk factor for diabetes.

Today, the numbers in the mandal have shot up, with 10.1 percent of the people suffering from diabetes. This is still less than the national average; diabetes in rural and urban India grew from 2.4 percent and 3.3 percent respectively in 1972 to 15 percent and 19 percent in 2015, according to a 2021 meta-analysis published in Annals of Epidemiology.

At 74.7 million people living with the disease, India is home to the second largest population of people with diabetes (after China). While the prevalence of diabetes is twice as high in urban India as compared to rural areas, Total Health has chalked it out to be one of the biggest causes of concern in Thavanampalle mandal, where its work primarily lies.

“I saw 600 people last month, of whom 200 had diabetes,” says Dr V Bhargav, who heads a mobile clinic unit. Most people who get diabetes are above the age of 50. Compare this to the national numbers: A 2009 study found that of the people living with diabetes, 54 percent develop it before reaching 50 years of age. The same study says that the onset of diabetes among Indians is about a decade earlier than their Western counterparts.

Changing diets

“The environment in rural India is changing, starting from what we eat,” says Dr T Swarna, who heads a satellite clinic in Thavanampalle.

In 2016, the authors of a study conducted in Krishnagiri in Northwest Tamil Nadu identified the primary factors that “have catalysed dietary changes leading to rising prevalence of diabetes”. Of course, there is the increased availability of ‘city foods’ such as sugar-laden sodas and sweets, as well as trans-fat-laced chips and bakery goods. But, more significantly, the availability of free polished rice at ration shops through the public distribution system (PDS) makes it the staple food of the region.

Less than 150 km from Krishnagiri, in Thavanampalle, doctors have observed a similar shift to rice as the staple. South India has a higher rate of diabetes compared to North India, possibly due to its partiality towards white rice, which has a high glycaemic index. When eaten as kanji (rice porridge) with the water it is cooked in, the starchy rice meal spikes blood sugar levels.

“The local feeling is that you are not full until you have had a rice meal,” says Dr M Gayathri, who heads our AYUSH clinic in Aragonda. The main aim is to keep hunger at bay, because not many people have the luxury of eating meat and fruit. Seasonal vegetables are affordable, but most plates are filled with rice and just a small portion of vegetables. A rice meal is filling and cheap.

“Farm labourers who leave for work at 8 in the morning, want a heavy meal that lasts through the day.”

Dr V Bhargav

Wheat is not locally grown, so rotis are not commonly eaten. Dr Swarna adds, “People believe chapatis cause heat in the body when had in the morning.”

Rice is replacing millets such as ragi, which used to be popular in Thavanampalle. “We still make ragi balls, but the ratio of ragi to rice flour (2:1) has reversed because of changing tastes,” says Dr Bhargav. Reddy is conscious of this. He says, “I include as many green, leafy vegetables in my meals as possible and have completely cut down on tea (most villages sweeten tea heavily).” However, he still depends on the PDS and can’t afford brown rice or red rice that were once regular traditional foods but have now become trendy ‘urban foods’, which has pushed up their prices.

“Before the Green Revolution in India, there were a hundred different varieties of rice in our diet,” says Jayanthi Somasundaram, head of Spirit of the Earth in Chennai (which promotes heritage rice), pointing to varieties such as thooyamalli, kaatuyanam, and mapillai champa. “Until the 1950s to ‘60s, there was a conception that white rice, consumed by the elite, was superior. For the middle class, who would have millets, white rice became aspirational,” she says. Krishna Prasad, founder of the Karnataka-based Sahaja Samrudha, adds that as milling technology improved, the more polished rice became, and the more aromatic and of higher quality it seemed to people. He recalls the Rayalaseema area of Andhra Pradesh in the 1960s: “Before it became popular for cash crops such as cotton and groundnut, the area, with its saline soil, used to grow many varieties of red rice.”

Over the years, diet isn’t the only thing that has changed, says R Indrani, another Thodathara resident living with diabetes. “I think the change in the crops we grow has also affected our lifestyle,” she says.

Thavanampalle has traditionally been famous for its sugarcane fields and the jaggery it produced. She adds, “We used to have a sugarcane field as well. But now there are very few of them left. Like most farmers here, we shifted to cultivating 10 acres of mango. Unlike sugarcane, which requires constant water and labour, the work in mango fields is seasonal and less intensive.”

“Unlike sugarcane which requires constant water and labour, the work in mango fields is seasonal and less intensive.”

R Indrani

The doctors at Total Health suspect that this reduction in physical activity combined with changing diets could be one of the contributing factors to diabetes. “I can’t eat the mangoes I grow,” Indrani says with an ironic laugh.

Screening for diabetes

Indrani found out she has diabetes only a year ago when she attended an eye screening camp. “People here are not that keen on regular testing. Unless they can physically see that there is a problem, such as frequent urination, they won’t come. Their attitude is not preventative,” says Dr Gayathri.

“Often, when they first come to us, their blood glucose level is already at 11 percent (the normal level is 6.5 percent). They could have had diabetes for many years but they may have just not known it,” says Dr Swarna.

In fact, about one in every two Indians in the 15–49 age group living with diabetes is unaware of their condition, according to a study conducted by the Public Health Foundation of India in 2019. Of those aware, only a quarter have it under control. The study also found that rural men are more susceptible to diabetes.

“One fear we see among people is the idea that once they start medication, they will have to continue taking it for a lifetime. People here don’t like becoming dependent on medicines,” says Dr Gayathri.

Doctors are unanimous in their view that the focus must be on pre-diabetes—its prevention and control. On the preventive health front, a traditional kitchen revival, where a more diverse diet is practised, and rice does not form the centrepiece, may help.

The more difficult challenge is the attitudinal shift towards movement. In Thavanampalle, as in many rural and urban areas in India, physical work is linked with class hierarchy. The more prosperous a family gets, the more help they can afford and the less functional their movements become.

Additionally, it is important to manage low- to moderate-risk diabetes in people to prevent it from turning into something more serious. As seen in the results of the national NCD survey conducted this year, adequate screening, conducting regular health camps, and increasing awareness about diabetes as a lifestyle disease is how people who have not yet got the disease can prevent it.

This article was first published in India Development Review on April 26, 2022.